With trading in May finished, we can look back at the month in its entirety and definitively say the old market adage,?Sell in May and Go Away? was wrong as could be. The month of May was the third straight month of positive returns in the U.S. equity indexes, the first such streak since August through October of 2007. The S&P 500 finished more than 5% higher for the month, in comparison to the 9.4% gain in April and the 8.5% gain in March. The rally in equities has indeed been impressive as the S&P is up more than 25% in the past three months, and an amazing 38% from the low point in early March.

It was not just stocks that enjoyed May, but crude oil also posted a huge 29% gain in May, its largest one month gain since 1999. The price of crude finished the month just shy of $67 per barrel, even as OPEC decided that no further supply cuts were necessary. Oil was not alone either as in general commodities were all propelled higher by the devaluation of the dollar. The basic materials index (IYM ) gained close to 14% on the month, which outpaced even gold, the traditional hedge against inflation as SPDR Gold Trust (GLD) was up about 10%. The combination of the dollar?s rapid decline and the prospect of economic growth on the horizon has propelled commodities to rebound quite strongly.

The question now is what to expect for the summer months ahead. At Ockham, we are not market timers and think that it is foolish for anyone to claim they know where the market is headed in the short term. However, here are some observations that we think may be important to keep in mind over the coming months.

The stock market is no longer cheap. An argument could?ve been made that the market was cheap in Feburary, March, and April, but it is increasingly hard to justify any longer. Remember, this is very different than saying the market is headed down, but we believe that the gains of the past few months are still vulnerable. According to Barron?s online, the S&P 500 is far more expensive than it was a year ago according to a standard price-earnings ratio. A year ago when the S&P 500 was in the high 1300?s the P/E ratio was about 22x, but given the massive declines in corporate earnings expectations Barron?s pegs the P/E at 123x! These numbers are as of May 25th so next week could go either way but you get the gist.

Our internal calculation of the S&P 500 valuation is not quite as extreme as Barrons, but it is hovering at about 46 times current earnings. Obviously, our earnings expectations have not fallen quite as far as Barron?s, but according to our estimates we are seeing earnings that have declined 79% since the peak in 2007 and 72% from one year ago.

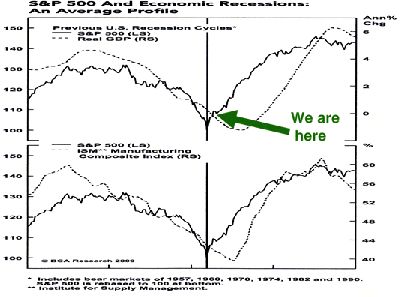

The fundamentals of equities have not improved in the last few months enough to justify these gains, in fact most indicators have not improved much at all but the perception is that the worst is behind us and growth will ensue. That may be the case, and we certainly hope it is, but it demonstrates to us that the market is currently trading on emotion and psychology rather than based on fundamental improvements. Investor sentiment and consumer confidence have both improved markedly over the past three months. The hope of better days ahead has been a powerful driver and could continue until corporate earnings truly do start to rebound. However, if the economy hits a bump and fear, uncertainty, and doubt start to creep back into the picture the recent market rally could very easily turn to dust because it was built on sentiment and not fundamentals.

Both sentiment and fundamentals are a completely legitimate and necessary components to market action, but in comparison to fundamentals, sentiment can be extremely fickle. How long can ?better than expected? be enough to carry the recent gains in the equity indexes? We are of the opinion that the current rally has been largely devoid of fundamental improvement, which makes it all the more vulnerable. At Ockham, we quote Ben Graham often, and this seems a very appropriate time to reference his *Security Analysis*: ?Stock markets behave like a voting machine in the short term, while in the long term they act like a weighing machine.?